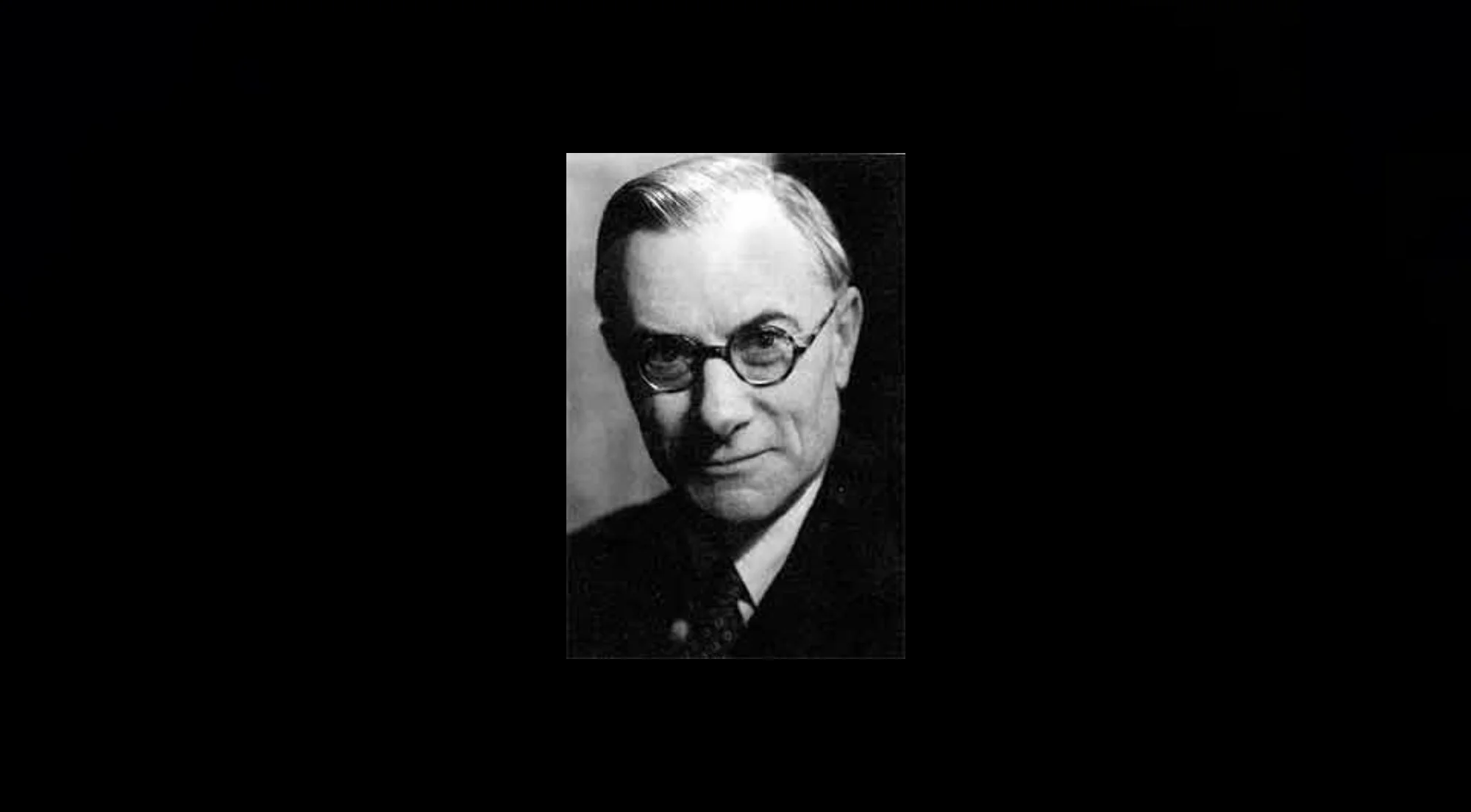

The linguistic turn of E. H. Carr: relativity, discourse, and meaning in The Twenty Years’ Crisis

Written by Matt Goolding

Matt is studying his Research Master’s in Modern History & International Relations at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. This essay was submitted in October 2023 as part of the Capita IRIO course.

Keywords: E. H. Carr; Twenty Years’ Crisis; Realism; International Relations; IR

Abstract: This essay argues that E. H. Carr’s The Twenty Years’ Crisis has value beyond its role as Realism’s origin story in IR. In fact, Carr’s relativistic mindset opens the door to the role of discourses, meanings, social constructs, and identities in international politics. His approach reflects contemporary critical scholarship in that it denaturalises dominant narratives, and in doing so, emphasises their capacity to maintain dominance.

Introduction

A brief summary of E. H. Carr’s The Twenty Years’ Crisis

While the point of departure for the discipline of International Relations (IR) and its emergent ‘paradigms’ is hotly contested (Schmidt, 1998), it is clear why E. H. Carr’s The Twenty Years’ Crisis—first published in 1939—is perceived to have influenced the development of ‘Realist’ thought. Although explicitly eschewing the ‘naked struggle for power’ of ‘pure realism’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 84), and seeking a balance between between realism and utopianism, the book robustly rejects liberal ideals, which Carr sees as having underpinned a doomed international political order.

In Carr’s mind, policies related to the harmony of interests, the common interest in peace, and laissez-faire economics were devised and implemented by an out-of-touch elite, ignorantly asserting the primacy of ethics over politics (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 42) and shoehorning the latter into the former. I argue, however, that rather than being ‘a Realist’ in the contemporary IR sense, Carr is instead employing what he calls ‘modern realism’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 63) (note: small-n) as a way of countering ‘the exuberance of utopianism’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 10).

In the face of what he calls ‘immature thought’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 10), the demise of the League of Nations, and ongoing Fascist expansionism, Carr is compelled to prescribe a dose of factual analysis; demanding an acknowledgement of the ‘strength of existing forces’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 10) as one step towards mitigating them. The existing force that has been ignored—willingly or otherwise—by idealists, Carr suggests, is power.

As a scholar, Carr isn’t easy to pigeonhole (Cox, 1999). Indeed, he has ‘puzzled more than one critic’ (Evans, 1975, p. 77), with the range of views on Carr 'testament to the complexity of his thought' (Molloy, 2003, p. 301). Furthermore, inconsistencies spanning his body of work cause some to complain that Carr ‘fails to provide a cogent and comprehensive theory of international relations’ (Howe, 1994, p. 277).

While I agree that Carr’s ‘diagnostic and critical’ (Morgenthau, 1948, p. 128) book does indeed contain the essences of what later became the Realist paradigm in its embrace of power ubiquity, this essay will highlight various underrepresented themes within The Twenty Years’ Crisis; themes which arguably have less in common with subsequent Realist thought than with the ‘linguistic turn’ in the social sciences.

Understanding Carr’s ‘relativism’ as fundamental to his argumentation

Carr’s ‘relativistic’ approach was, and is still, contentious—and has precipitated high-calibre incoming fire. Morgenthau, for example, claimed that Carr’s ‘philosophically untenable equation of utopia, theory and morality' results in a 'relativistic, instrumentalist conception of morality' (Morgenthau, 1948, p. 134). Hedley Bull, and others, too, followed with similar criticism (Howe, 1994, p. 278). This stems, in part, from Carr’s highlighting of ‘incompatibilities between personal, professional and commercial morality’ and his claim that international morality is a distinct category, ‘with standards which are in part peculiar to itself’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 143).

His acceptance that for pure realists, ‘morality can only be relative, not universal’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 19) could be seen as an admission, but Carr plainly refutes the extremities of that position. Others have pointed to the ‘crude’ and ‘superficial’ use of the sociology of knowledge (Molloy, 2003, p. 298) in accounting for ‘relativity of thought’ in political theory (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 65). Molloy argues that what was condemned by Morgenthau was in fact ‘exactly the form or morality that Carr was trying to promote—the notion of an absolute morality, based on eternal, a priori principles was anathema’ (Molloy, 2003, p. 299). Howe, too, claims that ‘fidelity to transcendent standards was part of the problem, not the solution’ (Howe, 1994, p. 280).

While I haven’t the space for an investigation into implications of Carr’s so-called moral relativism, I do see his explicitly relativistic ideas underpinning much of what relates to contemporary critical IR scholarship. Carr often foregrounds the subjective (relative) constitution of key concepts which are naturalised by idealism, and in doing so he uncovers non-neutral social constructions. In highlighting the ‘relativity of facts and values underlying social institutions’ (Heath, 2010, p. 30), Carr problematises the global order and presents examples of complexity, hypocrisy, and dynamic power imbalances—while acknowledging the (re)productive power of discourse in ways that get little attention in IR textbooks. Paradoxically, there is one universal, transcendent force. Power, according to Carr, is ‘an essential element of politics’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 97) and ‘a necessary ingredient of every political order.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 213). The inherency of power in international politics is perhaps the takeaway from The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and while Carr provides a breakdown of the different types of power, he does not explore its conceptual roots. We are expected to take power as a given; and uncomfortably, as a universal unquestionable truth. That said, I will now sideline this contradiction and highlight examples of Carr’s treatment of (re)productive discourses, social constructions, relative meanings, values, and identities.

Discursive, socially-constructed themes within The Twenty Years’ Crisis

In arguing for a balance between utopianism and realism in politics, Carr states that ‘the complete realist, unconditionally accepting the causal sequence of events, deprives himself of the possibility of changing reality.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 12). In this, Carr rejects ‘a predetermined course of development’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 12) and acknowledges the possibility of change; a role for agency in recognising the need for change—and the opportunity to deconstruct, and thereafter reconstruct non-static ordering principles. For Carr, the principles of utopianism, far from being natural and universal, were ‘historically conditioned’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 65). His ire is directed at the unquestioned acceptance of liberal norms, but that does not prevent us from learning a highly-transferable lesson for broader critical scholarship; to problematise concepts and explore their hidden constructions, relative meanings, and values—and to comprehend the various identity formations in play.

The power of representation appears regularly in The Twenty Years’ Crisis. Decades before Foucault popularised the reproductive nature of discourse, Carr repeatedly refers to a constructed reality. This is clearly evident in his reflections on the existence of an international community: ‘There is a world community for the reason (and for no other) that people talk, and within certain limits behave, as if there were a world community’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 147). While reflecting on the widespread personification of the state, Carr argues that ‘so long as statesmen, and others who influence the conduct of international affairs, agree in thinking that the state has duties, allow this view to guide their action, the hypothesis remains effective.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 140). In this account, discourse is productive; dominant figures are crafting and constraining our experience of reality. Relatedly, the utility of discursive representation is a consistent theme in the book.

Amid Carr’s reflections on purposeful thought (and the conditioning of collective thought), he describes how ‘theories designed to discredit an enemy or potential enemy’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 68) involve depicting them as inferiors.

More importantly, he highlights how these depictions change with the wind; Germans went from being efficient and enlightened in the nineteenth century to ‘coarse, brutal and narrow-minded’ after 1910 (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 67). He supports this with a quote from Bertrand Russell—himself a protagonist of the ‘linguistic turn’ in philosophy—who writes about how British society suddenly abandoned the habit of ridiculing the French after 1904’s Entente Cordiale. Carr then proceeds to introduce a semblance of binary identity development (i.e. defining the Self in terms of the Other); with the converse being ‘the propagation of theories reflecting moral credit on oneself and one's own policies.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 69).

Carr also reflects on the presence of norms and conventions in political order. ‘No political society, national or international, can exist unless people submit to certain rules of conduct’ Carr writes. ‘The problem of why people should submit to such rules is the fundamental problem of political philosophy.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 42). Power is the answer here, although his focus on the use of rhetoric, persuasion, and propaganda in the context of moulding public opinion suggests a more nuanced understanding of power than Realists tend to get credit for. Furthermore, Carr sees conventions as playing an ‘important part in all morality; and the essence of a convention is that it is binding so long as other people in fact abide by it.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 146).

On the binding nature of international treaties, Carr writes; ‘states which violate treaties either deny that they have done so, or else defend the violation by argument designed to show that it was legally or morally justified.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 142). He suggests that there is a sense of unseen obligation between states; something familiar to the ears of a Constructivist who may emphasise norm-induced compliance.

In a similar vein, the relative nature of meanings comes under scrutiny in The Twenty Years’ Crisis. For example, Carr contends that ‘few people do desire a ‘world-state’ or ‘collective security’, and that those who think they desire it mean different and incompatible things by it.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 9). While this argument is employed to discredit idealism, it nevertheless encourages us to think carefully about what we mean when we utilise such concepts in our own scholarship.

Carr’s distaste for domination is evident throughout. He sees universal narratives being mobilised by ‘a dominant group concerned to maintain its predominance by asserting the identity of its interests with those of the community as a whole’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 45). One such example is the assessment that ‘every nation has an interest in peace, and that any nation which desires to disturb the peace is therefore both irrational and immoral.’

This, he argues, is Anglo-Saxon-centric; ‘It was easy after 1918 to convince that part of mankind which lives in English-speaking countries that war profits nobody.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 50). Here we see the hallmarks of labelling and identification; something Carr suggests is reinforced by the ‘readiness of other countries to flatter the Anglo-Saxon world by repeating its slogans’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 51).

This echoes critical IR in two ways; an emphasis on the relationship between discourse and power, together with an appreciation for mutually constitutive identities. General principles, Carr argues, are ‘taken as an absolute standard, and policies are judged good or bad by the extent to which they conform to, or diverge from, it.’ (Carr & Cox, 2016, p. 14). This understanding of power dynamics (and the question of subversion vs compliance) would surely get the attention of any Feminist scholar in IR.

Conclusion

This is by no means an exhaustive account, but I hope to have provided an entry point for further investigation. As students, we’re encouraged to read eminent IR scholars as a rite of passage, but this is often framed more as a historiographical exercise than a journey of enlightenment. What I’ve learned through Carr is that the ‘old guard’ may have more to offer than merely satisfying our morbid curiosity for dead ideas. What we see in this book is more complex and nuanced than the ‘great debate’ narrative suggests.

Here, Carr is a specialist in contextualisation; he historicises the dominant political theory of his time as a means by which to critique it. Indeed, Carr’s reputation for historiography was solidified by his later works.

In summary, the value of The Twenty Years’ Crisis isn’t solely in revealing the origins of IR’s Realism, but in setting an influential precedent for the denaturalisation of dominant narratives. It shows how we must get to the root of political concepts rather than accepting them as essential. However, while Carr does acknowledge the limitations of realism, he does not problematise the concept of power in any meaningful way.

Eighty years later, and there is still no consensus about what the concept of power actually means (Drezner 2020).

References:

Carr, E. H., & Cox, M. (2016). The twenty years' crisis, 1919-1939: reissued with a new preface from Michael Cox. Palgrave Macmillan.

Cox, M. (1999). Will the Real E. H. Carr Please Stand up? [Review of The Vices of Integrity: E. H. Carr, 1892-1982., by J. Haslam]. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 75(3), 643–653.

Drezner, D. (2020). Power and International Relations: a temporal view. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 29-52.

Evans, G. (1975). E. H. Carr and International Relations. British Journal of International Studies, 1(2), 77–97.

Heath, A. (2010). E.H. Carr: Approaches to Understanding Experience and Knowledge. Global Discourse, 1(1), 24-46.

Howe, P. (1994). The Utopian Realism of E. H. Carr. Review of International Studies, 20(3), 277–297.

Molloy, S. (2003). Dialectics and Transformation: Exploring the International Theory of E. H. Carr. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 17(2), 279-306.

Morgenthau, H. (1948). The Political Science of E. H. Carr. World Politics, 1(1), 127-134.

Schmidt, B. C. (1998). The political discourse of anarchy: a disciplinary history of international relations (Ser. Suny series in global politics). State University of New York Press.